Local Privilege Escalation via Vulnerable USB Co-Installers

-

Finlay Richardson

Finlay Richardson - 15 Dec 2025

Finlay Richardson

Finlay Richardson Peripheral devices are a fascinating source of vulnerabilities in operating systems, and one that’s often overlooked. Following several vulnerabilities targeting the Razer Synapse USB co-installer on Windows, we wanted to determine if further vulnerabilities existed in the wider catalog of co-installers that are triggered upon connecting specific USB devices. Using a USB emulation device, it was possible to enumerate devices that triggered co-installers running in a high-privileged context, enabling more targeted vulnerability research. Several vulnerabilities were found, including one that could allow an attacker to escalate privileges from a low-privileged user to SYSTEM by planting a DLL and connecting a specific device.

Some hardware devices need the Operating System to install or configure additional settings for the support of non-default features. A great example of this is gaming peripherals, for example, the Razer Synapse co-installer is invoked when Windows installs Razer device drivers, ensuring that additional software components such as lighting control or macro functionality are registered correctly. This is accomplished by Windows’ “co-installer” functionality.

A co-installer in Windows is a dynamic-link library (DLL) that supplements the default driver installation process by handling device-specific tasks that SetupAPI, the Windows driver installation framework, cannot perform on its own. These operations often require elevated privileges because they may modify system services, write to protected registry locations, or install supporting applications. During installation, SetupAPI loads the co-installer and coordinates its execution at defined stages of the driver setup, allowing the vendor’s logic to extend Windows’ built-in Plug and Play handling without breaking the standard installation flow.

In recent years several privilege escalation vulnerabilities have been identified in co-installers, most notably within the Razer Synapse and SteelSeries GG co-installers. Some of these vulnerabilities were trivial to exploit - Razer Synapse and SteelSeries could both previously be exploited by connecting the relevant USB device, which spawned an installer GUI application with SYSTEM privileges. These GUI applications contained trivial “break out” vectors that could be used to spawn a command prompt with SYSTEM privileges: Video.

Since the disclosure of these high profile vulnerabilities, starting in January 2023 co-installers have been deprecated and are no longer signed by Microsoft. However, previously signed drivers that use co-installers still exist on modern Windows operating systems and can be triggered by connecting the correct USB device. Currently there is no published attempt to enumerate a wider set of USB devices for further co-installer vulnerabilities. Given the large number of registered USB vendors, the potential attack surface to identify similar vulnerabilities is large.

This left us curious: has anyone done a wider exploration of vulnerable co-installers, and if not, how could we emulate a wide variety of USB devices without having to buy thousands of pounds of gaming keyboards?

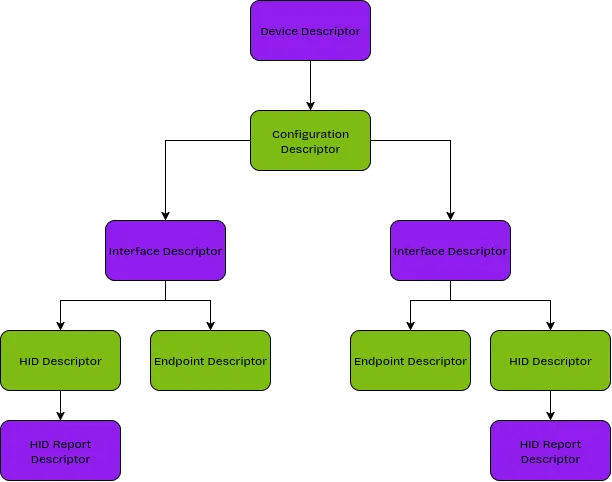

To trigger a co-installer, we must be able to successfully emulate a USB device in such a way that Windows recognises the device and installs drivers for it. The USB protocol employs a hierarchy of descriptors to describe a USB device’s functions and how a host should interact with it:

An example USB descriptor hierarchy

An example USB descriptor hierarchy

https://www.beyondlogic.org/usbnutshell/usb5.shtml

At the top of the hierarchy we have the overall Device Descriptor, that uniquely identifies the type of hardware. This is done with 2 key fields:

Vendor ID (VID): Identifies who made the device, e.g LogitechProduct ID (PID): Identifies the individual device within the vendor’s rangeAs can be seen in the diagram, a single device can offer multiple configurations, and multiple interfaces, that allow a single USB connector to offer multiple functions. At the bottom of the hierarchy, the leaves of the tree, are the Endpoint Descriptors and, for HID devices, HID Descriptors that tell the OS how to interface with it. All this information together tells the operating system what the device is, what functionality it offers, and how to use it, although for simplicity, a device can be uniquely identified via it’s VID and PID combination. Therefore, to emulate devices, we want to find a way to supply this info to the OS.

Using the Facedancer Python library and a supported hardware platform, we can programatically set these descriptors to be emulated, allowing low-level device emulation if needed. We used a Cynthion device from Great Scott Gadgets - this is a powerful USB testing platform that makes it really easy to perform all sorts of useful USB hackery. Here are some examples of cool things we can do with Cynthion:

from facedancer.device import USBDevice

device = USBDevice(

name=f"Emulated Device",

vendor_id=0x1234,

product_id=0x5678,

manufacturer_string="Reversec Labs",

product_string="Emulated Device",

serial_number_string="12345678",

device_class=0xEF,

device_subclass=0x02,

protocol_revision_number=0x01,

max_packet_size_ep0=64,

usb_spec_version=0x0200,

device_revision=0x0307

)

Example snippet of Facedancer code setting the device descriptor

So how closely do we need to emulate a vendor’s USB device to cause a driver to be installed, and trigger any co-installers to run? Windows installs drivers based on the hardware ID that consists of information parsed from the USB descriptors. You can use the pnputil tool or Get-PnpDevice to list the devices attached to a Windows system, showing their instance IDs:

$ pnputil /enum-devices /class USB /connected

Microsoft PnP Utility

Instance ID: USB\VID_1532&PID_0293\5&35f564d4&0&2

Device Description: USB Composite Device

Class Name: USB

Class GUID: {36fc9e60-c465-11cf-8056-444553540000}

Manufacturer Name: (Standard USB Host Controller)

Status: Started

Driver Name: usb.inf

$ Get-PnpDevice | Where-Object { $_.InstanceId -match "VID_1532&PID_0293&MI_" } | Select-Object InstanceId, FriendlyName, Status

InstanceId FriendlyName Status

---------- ------------ ------

HID\VID_1532&PID_0293&MI_01&COL03\7&22BAB829&0&0002 HID-compliant system controller Unknown

USB\VID_1532&PID_0293&MI_01\6&330B3579&0&0001 USB Input Device Unknown

HID\VID_1532&PID_0293&MI_02\7&3A7E446E&0&0000 HID-compliant mouse Unknown

HID\VID_1532&PID_0293&MI_01&COL04\7&22BAB829&0&0003 HID-compliant device Unknown

USB\VID_1532&PID_0293&MI_02\6&330B3579&0&0002 USB Input Device Unknown

HID\VID_1532&PID_0293&MI_01&COL05\7&22BAB829&0&0004 HID-compliant device Unknown

USB\VID_1532&PID_0293&MI_03\6&330B3579&0&0003 USB Input Device Unknown

HID\VID_1532&PID_0293&MI_03\7&16A706AC&0&0000 HID-compliant device Unknown

HID\VID_1532&PID_0293&MI_01&COL01\7&22BAB829&0&0000 HID Keyboard Device Unknown

HID\VID_1532&PID_0293&MI_00\7&69DAC00&0&0000 HID Keyboard Device Unknown

HID\VID_1532&PID_0293&MI_01&COL02\7&22BAB829&0&0001 HID-compliant consumer control device Unknown

USB\VID_1532&PID_0293&MI_00\6&330B3579&0&0000 USB Input Device Unknown

This tells us the following information:

1532, belonging to Razer0293, a specific model of keyboardIn addition, the device offers multiple interfaces (MI = Multiple Interface with zero-indexed value): MI_00, MI_01, MI_02, and MI_03.

Windows will use the VID, PID, and MI number to lookup the relevant driver & co-installer, and select the relevant .inf file to communicate with the device: Microsoft: Driver selection process, and so we can count these 3 fields as a unique identifier to represent devices. Windows interprets several different device classes, and other properties not listed in this example. But this research only considered HID and USB classes with these properties. We can see which drivers Windows selects for this device as follows:

$ Get-PnpDevice | Where-Object { $_.InstanceId -match "VID_1532&PID_0293&MI_" } |

>> ForEach-Object {

>> [PSCustomObject]@{

>> InstanceId = $_.InstanceId

>> Inf = (Get-PnpDeviceProperty -InstanceId $_.InstanceId -KeyName DEVPKEY_Device_DriverInfPath).Data

>> }

>> }

InstanceId Inf

---------- ---

HID\VID_1532&PID_0293&MI_01&COL03\7&22BAB829&0&0002 input.inf

USB\VID_1532&PID_0293&MI_01\6&330B3579&0&0001 input.inf

HID\VID_1532&PID_0293&MI_02\7&3A7E446E&0&0000 msmouse.inf

HID\VID_1532&PID_0293&MI_01&COL04\7&22BAB829&0&0003 input.inf

USB\VID_1532&PID_0293&MI_02\6&330B3579&0&0002 input.inf

HID\VID_1532&PID_0293&MI_01&COL05\7&22BAB829&0&0004 input.inf

USB\VID_1532&PID_0293&MI_03\6&330B3579&0&0003 input.inf

HID\VID_1532&PID_0293&MI_03\7&16A706AC&0&0000 input.inf

HID\VID_1532&PID_0293&MI_01&COL01\7&22BAB829&0&0000 keyboard...

HID\VID_1532&PID_0293&MI_00\7&69DAC00&0&0000 keyboard...

HID\VID_1532&PID_0293&MI_01&COL02\7&22BAB829&0&0001 hidserv.inf

USB\VID_1532&PID_0293&MI_00\6&330B3579&0&0000 input.inf

We can see that multiple drivers can be selected for each interface. This is done based on a specificity ranking. Armed with this knowledge, we can trigger the installation of specific drivers by emulating a device with a specific VID, PID, and an arbitrary number of interfaces using the following facedancer code:

def create_hid_device(vid: int, pid: int, num_interfaces: int):

configuration = USBConfiguration(

number=1,

configuration_string="HS Configuration",

self_powered=False,

supports_remote_wakeup=True,

max_power=500,

)

for i in range(num_interfaces):

interface = USBInterface(

number=i,

alternate=0,

class_number=0x03,

subclass_number=0x01,

protocol_number=0x02,

attached_descriptors=[mouse_hid_descriptor]

)

interface.add_descriptor(mouse_descriptor)

configuration.add_interface(interface)

device = USBDevice(

name=f"Emulated Device",

vendor_id=vid,

product_id=pid,

manufacturer_string="Reversec Labs",

product_string="Emulated Device",

serial_number_string="12345678",

device_class=0xEF,

device_subclass=0x02,

protocol_revision_number=0x01,

max_packet_size_ep0=64,

usb_spec_version=0x0200,

device_revision=0x0307

)

device.add_configuration(configuration)

return device

In this code, we use a generic mouse interface, but this doesn’t matter, as we’re purely interested in Windows’ response the VID,PID, and number of interfaces.

Now we can emulate arbitrary devices with our hardware and code, we need to find a strategy for hunting vulnerable co-installers.

Initially, the plan was to obtain a large list of USB vendor and product IDs, enumerate each one by one and log detected co-installers on a Windows machine.

Using a large list of USB devices supported by Linux, each device was emulated for twenty seconds, allowing Windows to recognise it and install the drivers. For drivers containing co-installers, device updates installed from the Microsoft Update Catalog were considered, as these were the case for the previous research. When these were installed, the installation and process of reading the .inf file was logged in C:\Windows\INF\setupapi.dev.log. By reading this file we could detect the inclusion of co-installers in the device update. The indicator of co-installer installation was:

Found legacy AddReg operation defining co-installers

This method turned out to be impractical for several reasons:

Using this method it was possible to enumerate 700 devices out of 11,591 in an overnight 9 hour run - with enough time we’d be able to analyse all devices, but with the time allocated for our intern project, this wouldn’t be fast enough. So we looked for a more efficient method.

Given that the delay of the first approach was waiting for Windows to trigger the update, download and begin installing it: why not try and download updates ourself?

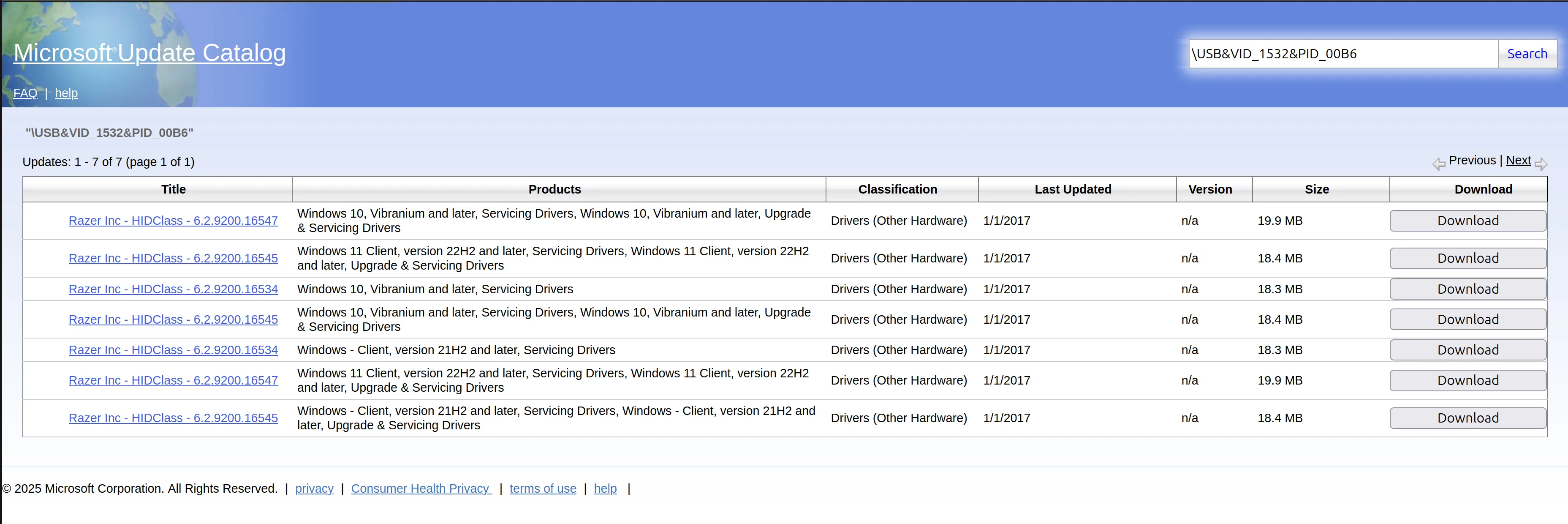

The Microsoft Update Catalog allows you to search for updates by USB vendor and product ID. Using the same previous list of USB IDs, we can search for each VID / PID combination, download the update file and use that to determine whether a co-installer is present.

Update files are provided as a .cab file, a compressed archive used by Windows. The start of each file contains the header and the file entries:

00000000: 4d53 4346 0000 0000 a5c3 3e01 0000 0000 MSCF......>.....

00000010: 4400 0000 0000 0000 0301 0100 a301 0400 D...............

00000020: 26a2 0000 1400 0000 0000 1000 a5c3 3e01 &.............>.

00000030: 2826 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 1f32 0000 (&...........2..

00000040: 9f03 0315 8078 0200 0000 0000 0000 d056 .....x.........V

00000050: 233c 2000 5261 7a65 7253 3253 3343 6f69 #< .RazerS2S3Coi

00000060: 6e73 7461 6c6c 6572 4578 2e64 6c6c 0080 nstallerEx.dll..

00000070: 7802 0080 7802 0000 00d0 5623 3c20 0052 x...x.....V#< .R

00000080: 617a 6572 5333 436f 696e 7374 616c 6c65 azerS3Coinstalle

00000090: 7245 782e 646c 6c00 809e 0200 00f1 0400 rEx.dll.........

000000a0: 0000 d056 243c 2000 5261 7a65 7253 3343 ...V$< .RazerS3C

000000b0: 6f69 6e73 7461 6c6c 6572 4578 3030 3931 oinstallerEx0091

000000c0: 2e64 6c6c 0080 9e02 0080 8f07 0000 00d0 .dll............

000000d0: 5624 3c20 0052 617a 6572 5333 436f 696e V$< .RazerS3Coin

000000e0: 7374 616c 6c65 7245 7830 3236 362e 646c stallerEx0266.dl

000000f0: 6c00 809e 0200 002e 0a00 0000 d056 243c l............V$<

00000100: 2000 5261 7a65 7253 3343 6f69 6e73 7461 .RazerS3Coinsta

00000110: 6c6c 6572 4578 3035 3238 2e64 6c6c 0080 llerEx0528.dll..

...

From the co-installers we’d enumerated so far, we saw that all of them contained a DLL with “CoInstaller” in the name, so this seemed like a suitable way of searching for CoInstallers. Using this search criteria, we only need to download the first few bytes of the update file to get all the information we need.

The first 512 bytes of the update file for each USB device were downloaded, by requesting those specific bytes in the HTTP header, and analysed for this criteria, which resulted in a list of 435 devices that contained co-installers. Along with collecting whether the update contains a co-installer, it was also possible to collect the valid hardware IDs relating to each VID/PID combination.

It would have taken an impractical amount of time to manually emulate all 435 devices and inspect, without developing further automation, so a strategy was employed to pick only one device from each vendor. This sped up the process and allowed the list to be narrowed down to a list of 13 “interesting” devices; where each device either:

This was monitored manually using System Informer to see what processes were spawned by each device. From our testing, we found the following interesting results:

Three devices were found to cause a BSOD upon the emulated device being plugged in and the driver being installed, potentially due to them not being fully functioning devices causing the drivers to fail. These were:

1926:00647392:C6110BDA:B023They displayed a WDF_VIOLATION error message relating to the attempted driver installation. Windows only attempts updates while the machine is unlocked with a user logged in.

The discovery of these scenarios capable of crashing modern Windows 10 and 11 systems simply by connecting a USB device highlights an important issue. The ability to trigger a BSOD so easily could opens the door to easy denial of service attacks on kiosks, workstations and shared devices. In high-availability environments such as healthcare, a malicious USB device could disrupt operations if the proper precautions, such as disabling automatic driver installation, are not taken.

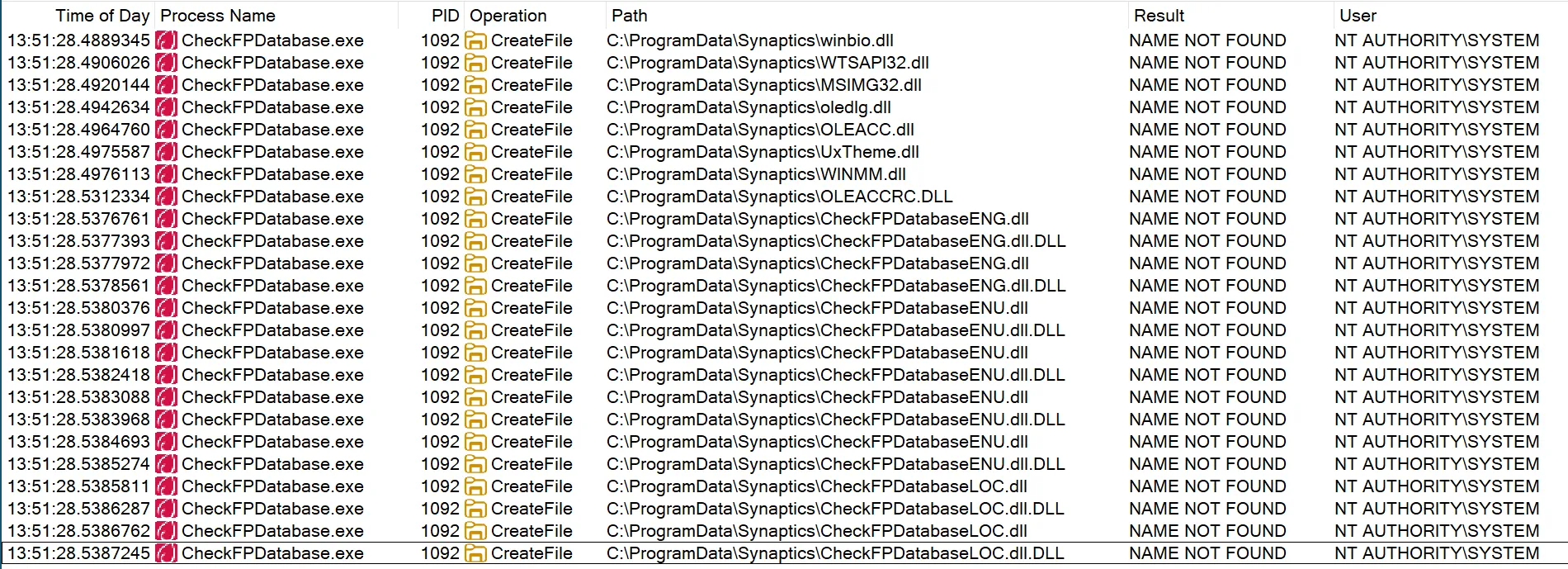

One of the more interesting devices was a Synaptics Fingerprint Biometric Reader (06CB:0082). Upon connecting this device, a co-installer was triggered that downloaded an executable called CheckFPDatabase.exe into the the C:\ProgramData\Synaptics directory and executed it as SYSTEM. By investigating the behaviour of the executable using ProcMon, it could be seen attempting to load several missing DLLs from the same directory that the program is running in:

As C:\ProgramData is writable by low-privileged users by default, this is a classic DLL hijacking vulnerability. To exploit this, an attacker would first create the folder C:\ProgramData\Synaptics and place their own DLL in that folder to achieve arbitrary code execution in a SYSTEM context.

You can read our full writeup at https://labs.reversec.com/advisories/2025/12/synaptics-biometric-reader-driver-co-installer-elevation-of-privileges for further information. We disclosed this vulnerability to Synaptics and it was assigned CVE-2025-11772.

Overall, the vulnerability can be exploited by an attacker with low-privileged access to a Windows system and the ability to connect a USB device to elevate their privileges. So we need physical access?

Well… yes and no.

Windows provides the ability to emulate USB devices in software through UDE. Unfortunately emulating USB devices in software requires elevated privileges. So you could exploit this without physical access, but not in a way that grants additional privileges.

What about VDIs?

Virtual Desktop Infrastructure (VDI) desktops are widely used in corporate environments, allowing users to log into company workstations. To allow employees to use peripheral devices within their VDI, some VDI providers (such as VMWare Horizon, Citrix) support allowing USB devices to be passed through to the virtualised operating system. In such circumstances, it would be possible to exploit USB co-installer vulnerabilities on those systems. As VDI machines are often shared with other users, this could enable an attacker to elevate privileges and target other users who are active on the VDI.

As mentioned previously, Microsoft has deprecated the use of co-installers, and no longer signs software that uses them. However, as we’ve shown there are a large number of co-installers that still exist on modern Windows versions. To stop the automatic installation caused by USB devices on machines, we can configure the registry key: HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\ setting this value to 1.

We disclosed the vulnerabilities we identified in Synaptics, and a CVE and patch was issued on 01/12/2025.

Additionally, detections aimed at identifying unsigned DLL loads from common user-writable directories will assist here: MITRE ATT&CK: Detection Strategy for Hijack Execution Flow for DLLs. You can see one such detection from Elastic here that aims to detect unsigned DLLs being loaded. Another strategy would be to look for suspicious USB device events (MITRE ATT&CK: DET0159, MITRE ATT&CK: DET0159), although in a large enterprise this is likely to be difficult to baseline, without a very strict USB device policy.

With additional research, there is significant potential for identifying further vulnerabilities. Windows supports many devices, including several that are very old, making it likely that there are other vulnerable co-installers.

Here are some key takeaways for various affected audiences: