Digital lockpicking - stealing keys to the kingdom

-

Krzysztof Marciniak

Krzysztof Marciniak - 11 Dec 2019

Krzysztof Marciniak

Krzysztof Marciniak In the era of smart devices, it should come as no surprise that more and more appliances “turn” smart. The KeyWe Smart Lock is no exception. In order to make life more convenient, it is designed to have both the mechanical lock mechanism and additional functionalities on top of it. Those include, but are not limited to, generating one-time guest codes and unlocking the door based on proximity.

Convenience does, however, always come at the cost of security.

The lock consists of three significant parts:

Both of the panels are connected; should someone attempt to disconnect them, an alarm will be set off. It can be opened in a few ways:

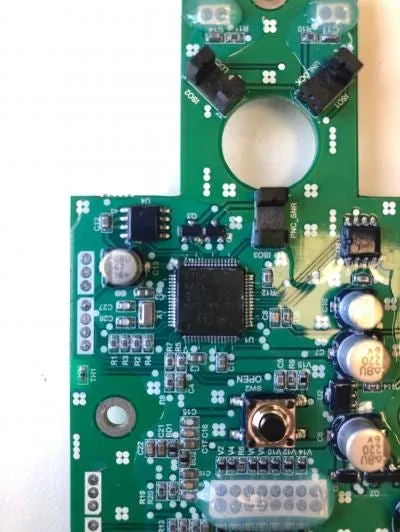

Removing the boards and inspecting them visually - without identifying the components - clearly shows the purpose of each of them.

KeyWe - boards

KeyWe - board (back)

The front one is used only to handle user input (numerical keyboard and the RFID chip). The back one, which is impossible to access by the attacker, handles all application logic. Serial and JTAG access attempts (on the latter) did not yield results. Component identification, however, showed an STM microcontroller is used. On one of the ports exposed SWIM - Single-Wire Interface Module, a debug protocol used in STM uCs - appeared to have been left enabled. After soldering to the pin and using the ST-LINK adapter it was possible to dump the device firmware. Although incomplete, the list of components identified on the board can be found below:

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| STM8L052R8 | Ultra-low-power 8-bit MCU with 64 Kbytes Flash, 16 MHz CPU, integrated EEPROM |

| Silicon Labs ZM5101A-CME3 | Z-Wave support (SoC) |

| adesto AT45DB021E | SPI Serial Flash memory |

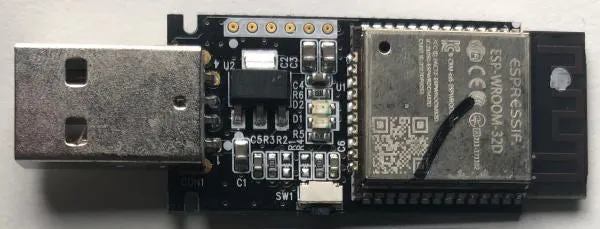

The bridge device is meant to expose the lock - which is handled via Bluetooth Low Energy - over WiFi. Though fairly sophisticated on the outside, inside it holds an ESP32-based board. The interesting part of this board are the pins located on the white panel.

KeyWe Bridge - board

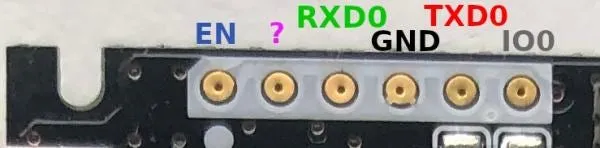

After spending some time with a multimeter and a pinout diagram, it was possible to identify most of the pins:

KeyWe Bridge - pinout

Although ESP is fairly mature - with read protections, encryption etc. available - no such functionalities are utilized by the bridge. The serial and JTAG access are left enabled, and no encryption is employed. This can be confirmed with the output below:

$ espefuse -p /dev/ttyACM0 summary

espefuse.py v2.5.1

Connecting....

Security fuses:

FLASH_CRYPT_CNT Flash encryption mode counter = 0 R/W (0x0)

FLASH_CRYPT_CONFIG Flash encryption config (key tweak bits) = 0 R/W (0x0)

[...]

JTAG_DISABLE Disable JTAG = 0 R/W (0x0)

[...]

Efuse fuses:

WR_DIS Efuse write disable mask = 0 R/W (0x0)

RD_DIS Efuse read disablemask = 0 R/W (0x0)

Given how easy it was to access the firmware, the bridge has not been given attention since the analysis.

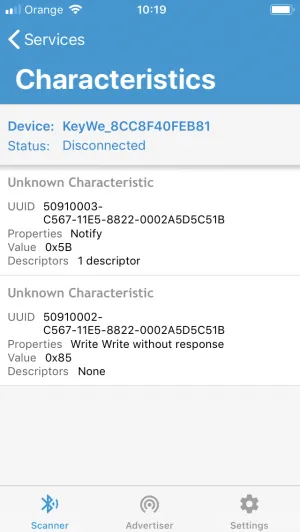

Let us go up a notch. Figuratively, of course. We are now moving to the communication and application layer. Based on publicly available materials, as well as the packaging with which the lock came, we know it uses “Bluetooth Smart”. For those unaware, this is just another name for BLE/BTLE: Bluetooth Low Energy. Probably the most convenient tool for BLE inspection is nRF Connect from Nordic Semiconductors (this is just an opinion of course). Before we proceed, this is a good time to recap on some basic concepts of Bluetooth Low Energy: Contrary to Bluetooth Classic, which is a technology we all know and most probably use every day, BLE does not work on the concept of discoverability (i.e. discoverable devices). Instead, each device (called a peripheral) sends out messages (called advertisements) to anyone close enough to receive them. An advertisement contains information about the peripheral: its name, address (used to establish a connection), features, and so on. Such a device exposes a list of grouped entities, called services. Those contain characteristics which can contain some value (text, number etc.) that can either be read (read access), updated (write access) or can notify the other connected party that the value has changed (notify access). The KeyWe lock exposes a single service with two characteristics - one read and one notify:

nRF Connect: KeyWe

We can already assume that they are used for sending/receiving messages to/from the lock. That being said, there is but one way to verify this: to inspect the mobile application. Due to personal preference, the Android application will be discussed.

Searching for BLE-related functions, we stumble upon the DoorLockNdk class, that contains multiple methods. For those not familiar with Android, NDK stands for Native Development Kit, and is a way to bridge native (compiled, unmanaged) code with Java (using the Java Native Interface, JNI). Each of the aforementioned methods returns an array of bytes - bingo! We have found ourselves a goldmine. To elaborate a bit more: if we somehow intercepted the messages, it would be for nothing; each message is encrypted with AES-128 before sending. With access to the DoorLockNdk class (its methods in particular), however, we can intercept messages before encryption. This means that the communication protocol can be analyzed. How do we intercept the function calls, though? The answer is simple… with Frida! Skipping the technicalities here (one can read more about function hooking with Frida here), we create functions that dump arguments and return values. The code can be found in the GitHub repository. A log of messages exchanged between the lock and the mobile application - based on the information gained using Frida - can be found below:

| Direction | Byte array | ASCII | Function name (if available) |

|---|---|---|---|

| lock <- app | bb b6 d4 26 36 c9 46 ea 4d 70 56 65 00 00 00 00 | …&6.F.MpVe… | makeAppNumber |

| lock -> app | c6 9b 84 8b 1c 18 1c 18 1c 18 1c 18 00 00 00 00 | … | (makeDoorNumber) |

| lock -> app | 48 65 6c 6c 6f 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 | Hello… | isHello |

| lock <- app | 57 65 6c 63 6f 6d 65 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 | Welcome… | makeWelcome |

| lock -> app | 53 54 41 52 54 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 | START… | isStart |

| lock <- app | 33 d4 02 01 10 11 03 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 | 3… | doorMode |

| lock -> app | 33 d4 02 05 10 01 00 00 00 11 03 00 00 00 00 00 | 3… |

Functions that deserve an honored mention are: makeCommonKey, makeAppKey and makeDoorKey. These are called, either within the application or on the lock, but do not directly result in messages sent. Although the exact thought process will be skipped, it should be pointed out that functions makeAppNumber and makeDoorNumber are used to generate values exchanged between the two parties. This serves as a simple “key exchange” protocol: each side generates a value, sends it to the other counterpart, and once the other “number” is received, the key pair can be calculated. One key is used to encrypt/decrypt messages originating from the lock (makeDoorKey) and the other for the mobile device (makeAppKey). Each of these numbers is encrypted with the common key before sending. A list of exemplary makeCommonKey call results - common key values - can be found below:

| Device address | Exec. ID | Byte array |

|---|---|---|

| 8c c8 f4 0f eb 81 | 0 | c8 8f f4 15 0f 4a eb 27 81 4a 6c 5e 67 41 ef ac |

| 8c c8 f4 0f eb 81 | 1 | c8 8f f4 15 0f 4a eb 27 81 4a 6c 5e 67 41 ef ac |

| 8c c8 f4 0f eb 81 | 2 | c8 8f f4 15 0f 4a eb 27 81 4a 6c 5e 67 41 ef ac |

| 8c c8 f4 0f ec 7b |

(exec. ID is used to state which execution - first, second etc. - it was for a given device) As we can (hopefully) see, the common key does not change between executions, but it does change with the device address. This is a grave mistake! As an in-house key exchange is used - with just two values involved - to decrypt all of the communication, one simply needs to intercept the transmission. The common key can then be easily calculated based on the device address. The code for calculating the keys has been released (although rendered harmless by removing key parts) in the aforementioned repository. With this, we have ourselves the keys to the kingdom!

The technical advisory for this vulnerability has been published here.

There is still one part missing from the puzzle. How do we actually get the messages exchanged between the lock and the mobile application? Regular applications/adapters do not have such a functionality. Fortunately, there is both hardware and firmware available to do it. In order to sniff Bluetooth LE traffic, one can use the nRF Sniffer available here. With a board such as Waveshare BLE400 or USB Armory Mk II (as it has an nRF-based Bluetooth SoC), gathering LE data is as simple as running Wireshark with one plugin installed.

The vendor has acknowledged the issue and is working on fixing it. They have been responsive since F-Secure disclosed the issue and have actively participated in communication. Unfortunately, no firmware upgrade functionality has been included and thus the issue will persist until the device is replaced. According to the vendor, new devices will contain a security fix. Moreover, the next version of the lock will have the firmware upgrade functionality - although no information is available regarding the release date.

One cannot say that no attention has been given to security with the KeyWe lock. The AES algorithm used is the de-facto standard when it comes to cryptography. But the protocol used can be referred to as in-house crypto - and, as the industry has shown over the years, this never ends well. Moreover, the vendor appears to have a vague idea of the threat model. Had the developers/architect(s) known that the device address is available to anyone close to the lock, there would be no issue whatsoever. The lessons learnt, and the takeaways for any organization dealing with smart, potentially IoT devices: